How to do your own research (kinda)

There are probably two types of people who clicked on this article. The first is your average person who just wants to make sense out of the conflicting and confusing information that is presented to them in the mainstream media, social media, or other sources who seem to use research to present completely contradictory views on fitness and nutrition. If this is you, maybe you were hoping to read this and come away with a fool-proof strategy that enables you to enter the correct things into Google to come away with the right answer to your fitness or nutrition question. The second kind of person, might be a graduate student who is curious how I possibly hope to condense the 6-15 credits of courses that they took, or are about to take, dealing with conducting research into a single article.

I sense a deep sense of disappointment in the near future for both of these groups. All hate mail should be directed to chris@blackironnutrition.com. BUT if any of the below questions get you excited, I urge you to read on. Here is what I WILL cover in this article:

How do I find the “right” research study?

How do I know if a source of information is using research properly?

How do I ask the right question?

What are the different types of studies and their strength and weaknesses?

What should I look for in the different sections of a research paper?

Where can I find relevant studies on exercise and nutrition?

How do I Find the “Right” Research Study?

So here is where the disappointment starts, and I think I am going to give an answer that people don’t expect, or necessarily want to hear. That is, unless you have specific training in how to read or interpret research IN THAT SPECIFIC FIELD, I do not think you should be seeking out individual studies in an attempt to make an informed decision on something. There are a few reasons why I say this:

There are literally hundreds of thousands of research articles published every year, so trying to go through primary sources and individual studies and trying to synthesize all the information into an actionable conclusion is going to be impossible for someone with no formal training. What you’d be trying to do with this approach is essentially a systematic review, which is difficult even for people with specific training.

In isolation, individual studies do not really give us much useful information unless you are already familiar with the most up to date research that led to that study. Research is an iterative process, every new study on a topic builds off the previous knowledge and work done in that topic. So if you just search for a topic and pick one of the more recent studies, it’s like buying a new book and starting in the tenth chapter and expecting not to be confused.

You can find an individual study that supports ANYTHING. Usually when researchers talk about a “significant” result, they are referring to something called a p-value being under a specified threshold. A p-value is a number between 0 and 1 that communicates the chance that the effect observed in the study is by pure chance alone. The standard threshold for significance is <.05, meaning that there is a less than 5% chance that the effect is due to chance alone. The problem is that with hundreds of thousands of studies published every year, there are plausibly hundreds that find significant effects that are due to random chance and not the actual thing they are trying to observe (Type I Errors). This is why reproducibility is so important.

Because of this, there are two groups of people reading this that I want to address somewhat separately, and these groups are distinguished by the level of effort and time they want to put into learning about the research process.

The first group are people who do not want to go through very much effort at all, and just want to understand how to separate the bullshit from the good stuff. I will call this group “normal people”, because most people have fulfilling lives and don’t feel the need to do silly things like write overcomplicated articles about research.

The second group wants to be able to go a little deeper and gain meaningful insights from studies they find or evaluate claims based on evidence someone is providing. I will call this group “nerds”, or in the words of the 21st century philosopher, J Balvin: “Mi Gente”.

Advice for Normal People

The first thing you need to understand is that the less you want to learn about a specific topic, the more trust you are going to have to put in others to get information. This is not a bad thing at all. In fact I think the whole idea of people “doing their own research” is often misguided, since most people do not have the tools to do their research, especially not in several distinct fields. Take myself for example, I do not “do my own research” when it comes to things outside of fitness and nutrition, because I know I do not have the background knowledge necessary to do so. I have a three-year-old son, but that does not make me an expert in childhood development and psychology. So you better believe that when my wife and I are having struggles related to the toddler years, I am going to consult experts in that field (shoutout to Ms. Rachel). Sure I could google something, or use “common sense”, but if I have learned anything from trying to become an expert in my field, is that those approaches are really prone to bias and leading you astray. Is relying on experts a sure fire way to be correct 100% of the time? Absolutely not, but you are going to be wrong much less often than if you tried doing your own research in a field you have no business doing your own research in.

When I say doing research in this context, I am talking specifically about seeking primary sources of literature for a specific claim or analyzing studies to try and come away with a conclusion on something. You can gain plenty of background knowledge from googling things, for example, I do not think you need a PhD to google “what are macros” and come away with accurate information.

Alright, so we’ve established that this first group needs to rely on external sources of information as opposed to seeking out primary sources, but how do they know who is reliable? Well, I want to provide some red flags and green flags that can guide you in assessing a source of information, at least within fitness and nutrition:

RED FLAGS

Red Flag #1: Someone whose brand is built on a specific way of training or eating. You see this a lot with “brand name” diets like keto, carnivore, paleo, etc. It’s not that these people have no useful or accurate information to share, it’s just that they are financially incentivized to never change their opinion on something. And any research they present to their audience is going to be through that lens and bias.

Red Flag #2: Similar to the previous point, another red flag is when someone promotes their strategy or philosophy as the end all be all for all goals and for all populations.

Red Flag #3: Anyone who uses the words “natural” “ancestral” or anything along those lines as support for why their claims are correct. There is nothing inherently wrong with things that are natural, but if the reason for suggesting something is just that it is natural, that does not tell us anything.

Red Flag #4: Anyone who seems to be contrarian to practically every piece of “conventional” nutrition knowledge. I am not saying that the conventional evidence-based nutrition field has it all right, but if it seems like someone refuses to believe ANYTHING coming out of mainstream science, that’s a red flag.

Red Flag # 5: When someone emphasizes cellular pathways, mechanisms, animal or in vitro models as the main source of evidence for their claims, without putting it into context with actual human outcome data. This one is a bit confusing at first, so let’s look at an example. I hate to pick on the carnivore crowd, but they seem guilty of this very often. Let’s take a look at a recent post made by one of these very influential figures, Paul Saladino. Despite his ironic surname, Paul has over a million followers and frequently claims that we should eat a carnivorous diet, vegetables are bad for you, seed oils will kill you, etc. Let’s break down what one of these claims might look like in the wild. In a recent Instagram post, he made the following claim that the seed oils in the brown rice at Chipotle would lead to bad health outcomes:

Lucky for us, Paul included a handy Pubmed Identifier (PMID) so that we can see the evidence of this claim for ourselves! Before we pull up the study, let’s ask ourselves: what are we looking for in this study based on this claim? The claim is that consuming seed oils which are high in linoleic acid cause people to get fat and sick by increasing HNE in the body. The sneaky part about this is there are multiple claims nested within this. We would want the referenced study to support the following assertions:

Consuming more linoleic acid increases HNE in the body.

Increased HNE in the body increases the risk of obesity and other forms of “sickness” in humans.

The amounts consumed in the diet pattern described (Chipotle) are sufficient to make point 1 relevant.

Alright, let’s look at the study.

This may seem daunting at first, but that is why it is important to understand what you are looking for before you open the study. Upon closer examination, the study was done in mice. You don’t need to know what any of the other stuff in this abstract says, because we are evaluating a specific claim. Now, I have nothing against animal models of research and think they are a very important part of the research process. But using a single mice study where they are fed isolated compounds, to make claims about this compound causing obesity and sickness in humans, is a HUGE logical leap and incredibly dishonest. It is especially dishonest, because we DO have research about seed oils in humans on a population level. So using animal models when more relevant research is available is fishy at best.

Green FLAGS

As I was writing this, I noticed I had much fewer green flags than red flags. I am not sure what that says about my attitude towards the social media fitness and nutrition community, but anyway…

Green Flag #1: This is going to be a bit counterintuitive, but when someone makes claims without too much confidence, and always ties the strength of their claim to the strength of their evidence. You’ll see these people use a lot of words like “probably” or “in most cases” or “this research suggests”, things like that.

Green Flag #2: When discussing individual studies, they put it in context with the rest of the research in that particular topic to try and give a holistic view of what the literature is telling us.

Green Flag #3: They give a ton of caveats to any claims they make. While this is annoying for someone just trying to get a simple answer to a seemingly simple question, there are almost always several layers of nuance that are important when putting out information to the general public.

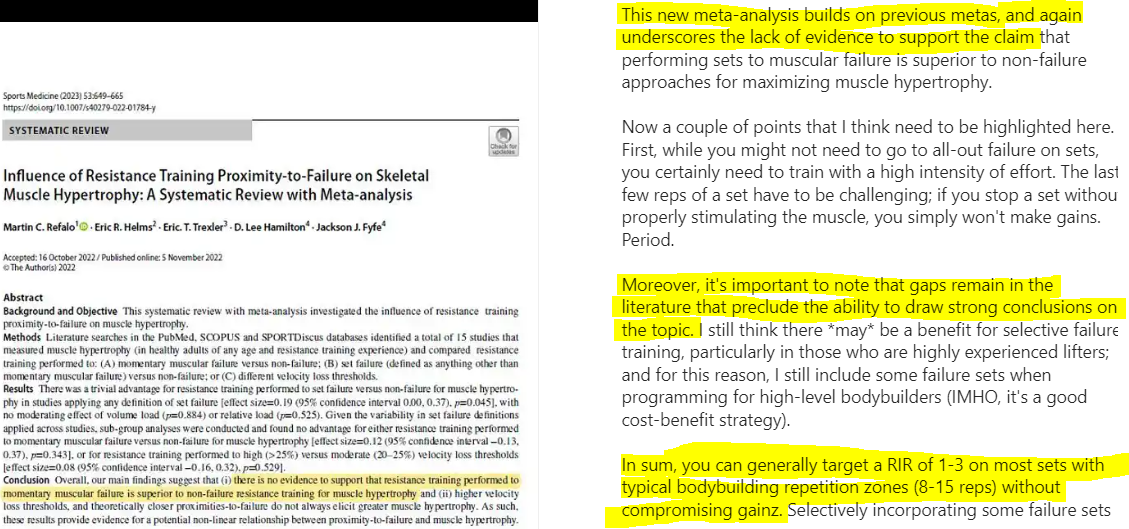

Let’s take a look at an example of communicating research done the right way. Below is a social media post by Brad Schoenfeld, PhD who is an exercise science researcher. In this post, he highlights a recent study that looks at whether training to muscular failure is better for muscle growth. The actual content of the study is unimportant for our discussion today, but let’s look at how he talks about it:

The very first thing Dr. Schoenfeld does here is identify the type of study it was (more on this later) and puts it in context with the rest of the literature on this specific topic. This tells the reader that we are not just looking at one study in isolation, but how this study fits in with all the literature. He then goes on to describe the limitations to the literature as a whole and how that may apply to how we implement this idea in real life, and to WHO. The last and most important thing he does is spell gains as “gainz”, which communicates that Dr. Schoenfeld is down with the youth and not just some pencil-necked scientist who hasn’t lifted a day in his life.

So those are a few things we can look out for when we come across research communication in the wild and don’t want to really dig too deep into study design, statistical analysis, or anything like that. Now, for the fun part!

Advice for Nerds (Mi Gente)

For this group, we are assuming that you are a little more willing to get into the nitty gritty of the research process, and maybe try and read some full-text research papers. There are a few steps I suggest taking when encountering a research study.

The VERY first thing you want to do is to ask yourself: What is the question you are trying to answer by reading this study? Is it an answerable question? A useful way to structure your question is using the PICO framework, which stands for:

Population- Are you interested in finding out about a certain effect in weightlifters, general population, people with Type II diabetes, etc.

Intervention- What is the thing or action you are analyzing for an effect?

Comparison- What are you comparing the effects of that thing to?

Outcome- What is the variable you expect the intervention to have an effect on?

So let’s give an example. Let’s say I am interested in finding out if saturated fat consumption increases the risk for heart disease in men over the age of 55. So my (P) population is men over 55, my (I) intervention is high saturated fat intake (which is important to define what “high” means), my (C) comparison would be low saturated fat intake (again, important to define), and my (O) outcome is rate of heart disease.

Different Study Designs and Their Strength and Weaknesses

Once you have a clearly defined question you want to answer, and have a study up on your computer, the next thing you want to do is determine the type of study you are looking at. All studies are not created equal in terms of the strength of evidence that they have the potential to provide. Below is what we call the “hierarchy of evidence” when it comes to research designs. The designs toward the bottom of the pyramid are lower forms of evidence due to the higher risk of bias, lack of experimental control, or lack of ecological validity (as is the case with animal models).

We covered animal models a bit thanks to our carnivore example, so let’s skip ahead to the more common study designs we see in fitness and nutrition.

Cross-sectional studies- This is an observational type of research that analyzes data from a population at a specific point in time. So for example, you could pick a population you are interested in and seeing if they are more likely to have X outcome. Continuing with our PICO question from earlier, a cross-sectional study looking at this would take a bunch of men over 55 look at their current saturated fat intake and whether they have heart disease or not. While this type of study is a bit easier to conduct, it is limited in the sense that we can only draw correlations with this data and are limited in our ability to draw causal links. For example, this type of study may show us a greater rate of heart disease among “high” consumers of saturated fat, but that relationship could easily be due to other characteristics that are different between “high” and “low” consumers. Maybe high consumers consume much less fiber than low consumers, and that has an effect on heart disease independent of the level of saturated fat intake.

Cohort Studies- Another type of observational study design is a cohort study, which can be either retrospective or prospective. A retrospective design takes a group of people (men over 55 in our example) and looks backward in time. So we’d be looking at our groups of men over 55, taking their historical medical records and looking for things that tend to be more common in your subjects that currently have heart disease versus the ones that do not. A prospective study on the other hand recruits subjects before they get heart disease, follows those subjects for a certain amount of time and sees which ones get heart disease. Prospective studies are generally seen as higher quality, because there is less risk bias. One of the most famous prospective cohort studies is the Framingham Heart Study, which has been following residents of Framingham Massachusetts since 1948 and analyzing trends and patterns of cardiovascular disease and associated risk factors.

Randomized Control Trials (RCTs)- This is typically touted as the “gold standard” of research designs as it controls for the most variables and gives us the most accurate look at the outcome of interest as possible. In our example, this would be like having two groups locked in a metabolic ward, feeding one a ton of saturated fat, and the other less saturated fat, waiting several years and seeing which group has a higher prevalence of heart disease. As you can tell, this type of study is really difficult to do with some of the questions we ask in nutrition, since the outcomes we are interested in take decades to develop and have complex interactions with the exposure we are interested in (saturated fat intake in our example). What you could possibly due, is conduct an RCT to see if saturated fat intake in a meal raises certain markers that are associated with heart disease after that meal, but there are significant limitations to that. Every time you use a proxy measure, or try to extrapolate short-term outcomes to long-term ones, you are adding assumptions that may not be valid.

Meta-analysis/Systematic Reviews- This is when you compile all the research in a given area, with a given inclusion criteria, and analyze the data in aggregate to see where the research is indicating the effect is. This provides much more statistical power than any one study could, since it helps eliminate the effects that can come from single studies by looking at them as a whole.

It is important to note that this hierarchy does is not definitive. For example, a well conducted prospective cohort study could be much more useful in some cases than an RCT.

Components of a Research Paper

Now that you’ve identified the type of study you are looking at, you can start reading, yay! Research papers usually have a similar structure, so let’s go through some of these common sections and pick out what we should see in them and what parts are useful for our purposes.

Introduction- The main goal of the introduction section is to build a clear rationale based on previous research and then present the purpose and hypothesis of the paper. To accomplish this, the authors of the paper start with the most basic concepts, which apply to the specific study, then establish a problem and thus, the need for the present study. This section can be a great way to gain a background on a topic if you are unfamiliar with it (assuming it is well-written).

Methods- The most important overarching goal of the methods section is that it is supposed to provide the reader with clear enough information that they could reproduce the study themselves. Components of the methods sections are usually:

Subjects. It is important that there is a detailed explanation of the subjects descriptive statistics for the factors that you would want to be the same between groups at baseline. For example, if we are looking at saturated fat intake and heart disease, you would want the two comparison groups to be as similar as possible in all other factors that also affect heart disease (age, BMI, waist circumference, etc.).

Experimental protocol/methods of data collection

Statistical methods planned.

Results- This section is exactly what it sounds like, an objective view of the results of all the statistical tests that they told you they were going to do in the methods section. This section is going to have a ton of numbers and results of statistical test that, unless you are familiar with them, are going to confuse you. If you really want to start understanding some common statistical tests to better understand this section, a good place to start is with a membership to Laerd Statistics which has amazing breakdowns of key concepts and test. This will not make you an expert, but it may take away some of the mysticism shrouding some statistical tests and concepts. Unless you have that familiarity, I would just try and extract what the main significant results are and keep those in mind as you head to the next section.

Discussion- This is probably the most important section of a paper if you are looking for the “so what” of the paper. In this section the authors will restate their purpose and main findings, interpret their results and compare their findings to previous literature looking at the same topic, talk about limitations of the study (every study has them), and then sometimes have some talk about practical applications and further research that is required.

Where can you find relevant studies on exercise and nutrition?

This depends on what you are trying to achieve by reading research. If you have a specific question you are trying to answer, I would advise looking at position statements from the relevant organizations as a starting point, if they are available. These are developed with the most recent research and practical guidelines in mind, and are developed by leading experts in that specific field. If you want, you can also dig into the specific studies that are referenced in them as well. For example, following with our heart disease question, you could go to the CDC’s website and they have several sections related to heart disease risk factors.

If you just generally want to continue learning and stay up to date on research in a particular topic, I am again going to advise against going and looking for individual studies on pubmed or google scholar, BUT there are some research reviews out there that can be a really good entry point for not only seeing new studies that are relevant to your interests, but who also walk you through the research interpretation process.

For specifically strength and conditioning interests, there is the Monthly Applications in Strength Sports (MASS). I cannot recommend them enough, they do fantastic work.

For more general health related stuff but still with a strength and conditioning slant, Barbell Medicine does podcasts and article research reviews a few times a month.

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) has an Exercise and Sport Science Review online, with most of the articles being open access. They have a good mix of general health and exercise science stuff.

Layne Norton does a pretty good monthly research review called REPS, which is focused purely on nutrition, and addresses most of the “hot topics” you see on social media.

Conclusion

If you made it this far, I officially consider you a friend of mine. Research is complicated, and misinformation is often much simpler and more alluring than the truth, which is often nuanced. I will leave you with this quote:

“A lie can travel around the world and back again while the truth is lacing up its boots. – Mark Twain.” -Michael Scott

Written by: Chris Bonilla, Black Iron Nutrition Performance Coach