The Black Iron Run + Lift Program

In case you’ve been living under a rock, Black Iron Training has recently released a revolutionary new training program that asks its subscribers to do what has previously been considered forbidden or just downright foolish: combine lifting and running into ONE program. The lifting and running worlds alike have been rocked by this development. Government agencies have been brought to a standstill by the flood of concerned citizens calling their local representatives urging action against such an irresponsible product on the market. Bodybuilders shield their eyes and avoid the internet which is exploding with talk of this program, lest even the sight of someone running cause an immediate shriveling of their quads. Streets in major metropolitan areas world-wide are barren as everyone is glued to their televisions, anxiously awaiting guidance from their government on how to live in a post Run + Lift world. Finally, after intense deliberation, the United Nations releases official word to the world’s citizens via fax machine (all other technologies have fallen in the chaos). A single sheet of paper slowly emerges from every fax machine in the world, with a single instruction:

Sign up here: marketplace.trainheroic.com/workout-plan/team/run-lift

My Background and the Birth of Run + Lift

Hi, my name is Chris Bonilla, and I write the programming for the Run + Lift program. Growing up, I played soccer competitively until about high school when I realized I just was not very good at it. In a desperate scramble to find a physical outlet, I eventually decided to join the Army National Guard as an infantryman at the ripe age of 17. Preparing for military service in the year that followed sparked a true passion for all things health and fitness related, and since then I have coached weightlifting/CrossFit/nutrition in some capacity in an effort to share that passion with those around me. When I was 20, I got introduced to the sport of weightlifting. Having quite an obsessive personality, the sport instantly sucked me in and took over my life for the following six years. Eventually, injuries and burnout caused me to quit the sport. Naturally, I then transitioned to a sport with an even greater time commitment and rate of injury, on the complete opposite end of the athletic spectrum: the Ironman triathlon. After 18-months of training, I completed Ironman Maryland (the flattest course I could find). During this period, I did not lift at all (hence the drastic difference in the pictures below). Partly because of the extreme time commitment needed for running/biking/swimming, but also partly because I couldn’t stand the barbell anymore.

Here's a picture at my last ever weightlifting meet (2019), and the Ironman finish line (2021):

(My actual time was 15:15 but we were on a staggered start).

Once the Ironman was complete, I knew I had to stop going to the extremes in my fitness if I wanted to have any sort of longevity and sustainability. However, knowing myself, I know I get restless if I am not in full obsessive pursuit of some grand goal. This lead to me throwing myself into a Master’s in Exercise Science, and eventually a Ph.D in Exercise Science. I figured if I barely have time to work out, I can’t possibly overdo it (checkmate, self!). Now, with limited time and energy to devote to working out I needed to find a way to stay aerobically fit, but also be strong like I was in my younger years. Thus, the Run + Lift program was born.

But Aren’t Running and Lifting Contradictory Goals?

If you’re a lifter, you’ve no doubt heard that cardio kills your gains. If you’re a runner, you’re probably familiar with the argument that lifting makes you bulky and slow. So, what’s the deal there?

Running and lifting are indeed two separate disciplines with their own unique set of adaptations and training requirements, which has caused many to be worried about something called the “interference effect”. The interference effect refers to the proposed negative effect that endurance training has on strength, power, and hypertrophy outcomes. This study was influential in developing this idea, as it did find that strength gains were attenuated in the concurrent training group compared to the strength-only group. But it’s important to understand the specifics of this study before we overgeneralize conclusions.

In this study there were three groups: 1. A strength group that exercised 30-40 min/day, 5 days/week 2. An endurance group that exercised 40 min/day, 6 days/week. 3. A Strength and Endurance group that simply combined the exercise regimens of the other two groups. For the first 7 weeks of the study, strength improvements in the concurrent training group tracked pretty closely with strength gains in the resistance training-only group, but levelled off and started to decline in the last three weeks of the study. So their conclusion was that these findings demonstrate that simultaneously training for strength and endurance concurrently will result in a reduced capacity to develop strength. However, think about what the combined group were doing for a second. They were doing 11 sessions per week, 5 lower body lifting sessions and 6 40-minute endurance sessions. I think most people would not be able to tolerate that sort of volume and would experience decreases in their strength simply from inadequate recovery.

Since then, dozens of studies have been conducted on this topic with increasing levels of nuance and complexity. This handy meta-analysis from 2022 gives us an updated look at the state of concurrent training research. In summary, concurrent aerobic and strength training does not seem to compromise muscle hypertrophy or maximal strength development, but there does seem to be an overall effect on explosive strength gains. The important thing to remember in all of this is that the dosage makes the poison.

On the extreme ends of the spectrum, the interference effect is more relevant. Most concurrent training studies do not look at participants who are trying to push the absolute limits of human performance in either strength, power, or endurance. So, if that describes you, and you are willfully sacrificing long-term health for the attainment of athletic glory as elite athletes often do, then maybe you need to be more careful when considering the implementation of concurrent training. However, for most of us, the interference effect is not that big of a deal. You can get really strong and really aerobically fit with the proper effort and programming. And in fact, it would benefit you to do so.

The overall health benefits of concurrent training, apart from muscle function and size, appear to be greater than those obtained with isolated training of either aerobic or strength training. Therefore, most individuals, including recreational athletes, can enjoy complementary benefits from incorporating both aerobic and strength training into their training program.

How Can we Balance Running and Lifting?

From a programming perspective, we can’t just mash together a marathon training plan with a powerlifting one without consideration as to how those two interact with each other. So, to answer this question, we need to first understand some important concepts when it comes to training volume. In general, we get more adaptations with more volume. But that only works up to a point, after which any further training has a detrimental effect. This continuum can be characterized by three volume landmarks: maintenance volume (MV), minimum effective volume (MEV), and maximum recoverable volume (MRV).

MV refers to the amount of volume that is necessary to avoid a de-training effect. The good news is that MV is much lower than the volume that is needed to see meaningful improvements, which is your MEV. This is particularly useful for our purposes since we are aiming to become the best at multiple competing athletic qualities all at the same time. Our bodies have a finite amount of resources which it can use to recover from training, so any volume we devote to training one quality will naturally come at the cost of training another. However, if we keep the volume at or slightly above MV for those qualities we are not focused on, we can minimize any de-training effects. Lastly, MRV is simply that point where increases in volume stop being useful and you get less adaptations with every increase in volume. Depicted visually:

Points A and B represent two amounts of volume that elicit the same amount of improvements. Point A does so while devoting less volume and recovery resources, meaning that more volume can then be allocated to other exercises or athletic qualities. While getting closer to or even slightly over our MRV will give us better improvements, training to improve both running and lifting means we need to be a bit more stingy with our training volume than someone focused on just one of those.

So how does this all factor into the Run + Lift program?

The Structure of the Run + Lift Program

All the concepts above drive how the Run + Lift program is structured and planned at the annual level. The volume and intensity of running and lifting need to ebb and flow in a reciprocal manner over the course of the year. At certain times of year, we are focusing more on strength gains while our running is put more towards a maintenance dose. Other times of year, that relationship switches. This is accomplished through a manipulation of volume, intensity, and frequency of each type of training. Here is a general outline of how the year goes on the program:

Weeks 0-8: Hypertrophy and strength emphasis / Aerobic build

3x/week lifting (strength, hypertrophy, power days).

2x/week running (building run distances)

Weeks 9-16: Strength Power / Run intensification

3x/week lifting (Lower volumes, higher intensities)

2x/week running (Longer intervals, higher overall intensity).

Weeks 17-25: Strength Power / Run intensification II

2x/week lifting (power day, strength day, ~5 rep range for major movements)

3x/week running (Longer intervals, more overall mileage with an extra run day).

Weeks 26-34 : Strength Power / Run intensification III

2x/week lifting (power day, strength day, focus on maintenance of strength)

3x/week running (Continue building higher intensities and durations).

Weeks 35- 43: Strength Focus / Run Maintenance

2x/week lifting (power day, strength day, building volume on strength movements)

3x/week running (shift to mostly easy efforts, but still high volume).

Weeks 44-52: Power Focus / Run Maintenance

3x/week lifting (Strength, power, hypertrophy days. Pushing intensity in the 3-6 rep range with plenty of accessory work).

2x/week running (Volume comes down to maintenance dose to focus on lifting).

In between each of these phases, we conduct a “benchmark week” in which we complete periodic assessments of strength and running to give a holistic view of your current fitness and progress. The assessments we use are:

3RM Deadlift

3RM Squat

3RM Bench Press

3RM Overhead Press

Run of choice (5k, 10k, half marathon)

Does the Program Even Work?

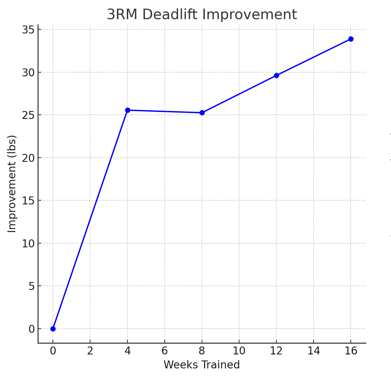

I am glad you asked! In 2023, I conducted a study that used a training program VERY similar to the one that became the Run + Lift program to improve strength and running outcomes. The specific assessments were a little different, instead of the above assessments we used a 3RM deadlift, 2-minutes of pushups for max reps, and a 2-mile run. It ran for 16 weeks of 5x/week training (2x lifting, 3x running) and had 18 total participants (10 male, 8 female). Here are the results:

Average deadlift 3RM improvement: 34lbs

Average increase in pushups in two minutes: 12 reps

Average 2-mile run improvement: 2 minutes 36 seconds

If you want more details, you’ll have to wait until it’s officially published 😊.

So there you have it, the Run + Lift program and the planning that goes on behind the scenes. If you want to know more, or have any questions, shoot me an email at chris@blackironnutrition.com and I will be glad to help.

Written by: Chris Bonilla, Black Iron Training & Performance Nutrition Coach